This site presents television and newspaper archives documenting Frithjof Schuon’s indictment, and its dismissal, in 1991. Schuon was indicted by a grand jury for child molestation on October 15, 1991 and the indictments were dismissed by the prosecutor a month later on November 20, 1991. Schuon (1907-1998) is best known for a philosophy described by the title of his first book, The Transcendent Unity of Religions.

A number of online “dossiers,” blogs, and sites contain inflammatory accusations against the philosopher. In the American judicial system, the dead cannot be defamed. Thus, there are no legal remedies to what appear to be libelous accusations. To complicate matters, newspaper and television accounts are relatively inaccessible because they are in archives created before the era of online, digital media. The intention of this site is to provide unbiased, independent, contemporaneous accounts of the facts of Schuon’s legal ordeal and to allow readers to form their own conclusions.

Television accounts

The Frithjof Schuon indictment led to a number of television news reports, as well as interviews with Schuon himself. The video clips below appeared in a documentary shown on two television stations in December 1991:

In this first video clip, Schuon discusses his legal ordeal of 1991 with a newspaper reporter. It also provides some background on the development and dismissal of the indictment, and includes video clips that were shown on local stations immediately after the indictment:

The second clip is from the same 1991 session with the reporter. In it, Mr. Schuon summarizes the essential aspects of his philosophy that provide insight into his principles and his attitudes towards morality:

Newspaper accounts

The Frithjof Schuon indictment, and its quick dismissal, was covered extensively in local newspapers. Most of these newspaper accounts are available on this site in both graphic files and searchable text. Clicking on the title of one of the articles in the table below will allow you to view one or the other. The items can be expanded by clicking on either an article image or an article text.

We have redacted (i.e. blacked out) addresses as a courtesy to people mentioned in them.

| October 16, 1991 | Abuse charges aired, denied |

| October 16, 1991 | Schuon well known among religious scholars |

| October 18, 1991 | Schuon’s writings extensive |

| October 20, 1991 | Schuon known as an ‘eminent thinker’ |

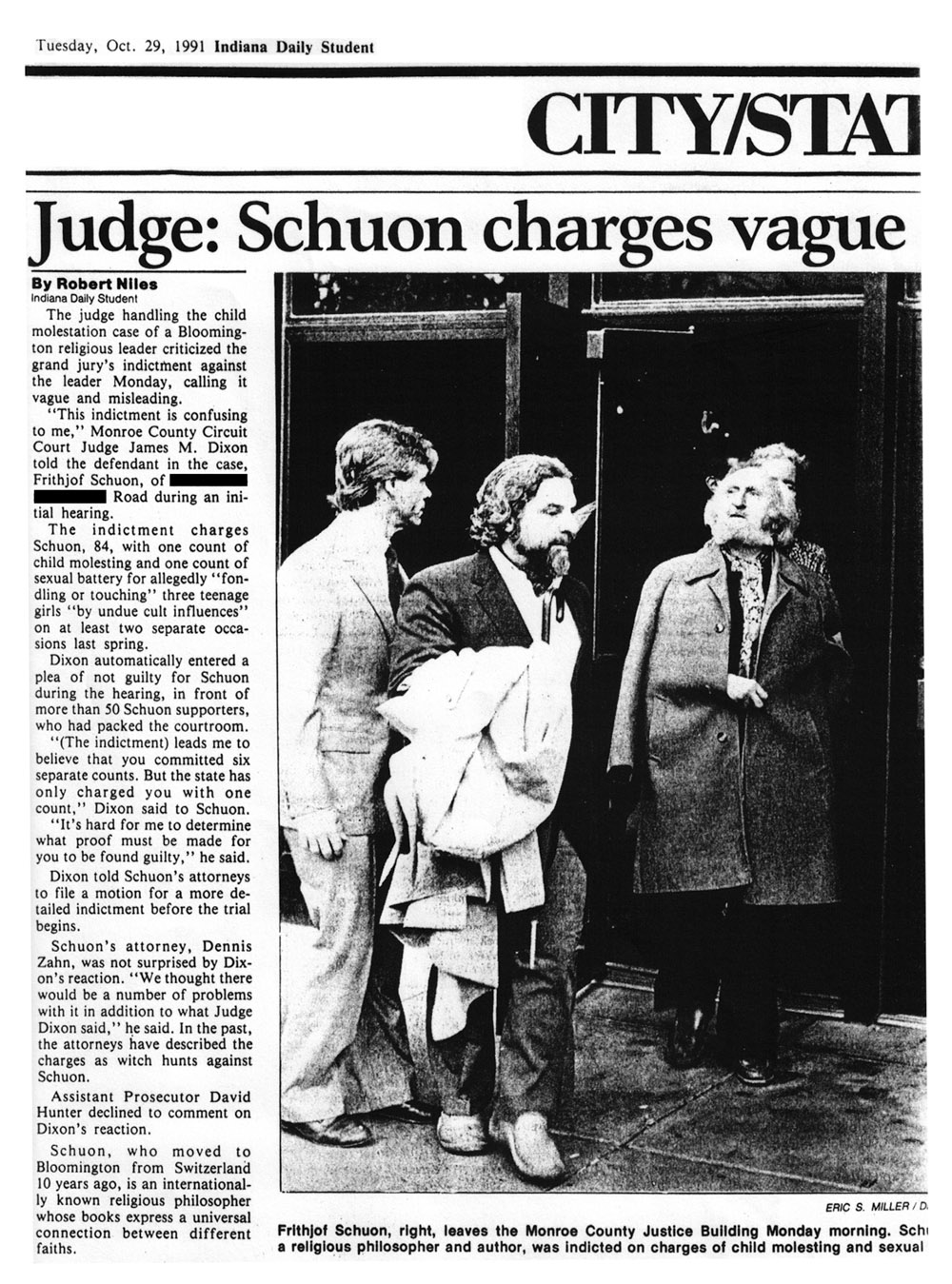

| October 29, 1991 | Judge: Schuon charges vague |

| November 1, 1991 | Charges ‘bizarre’ |

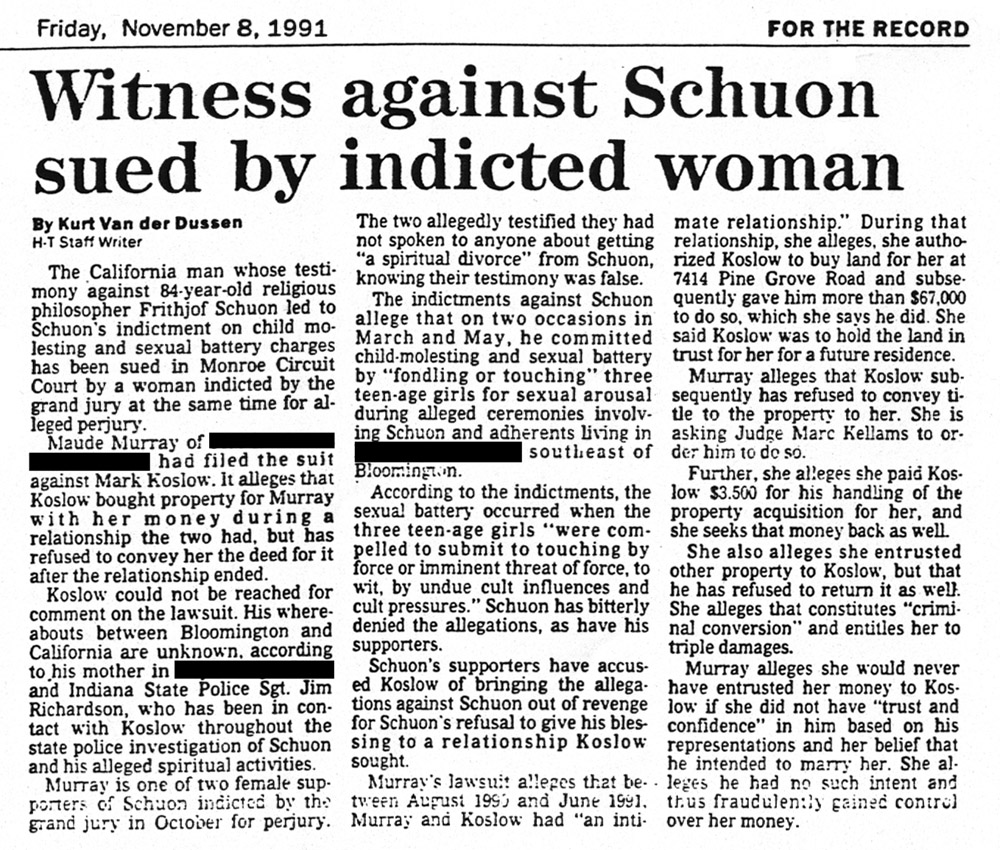

| November 8, 1991 | Witness against Schuon sued by indicted woman |

| November 21, 1991 | Schuon indictments dropped |

| November 21, 1991 | Schuon happy ‘nightmare’ is over |

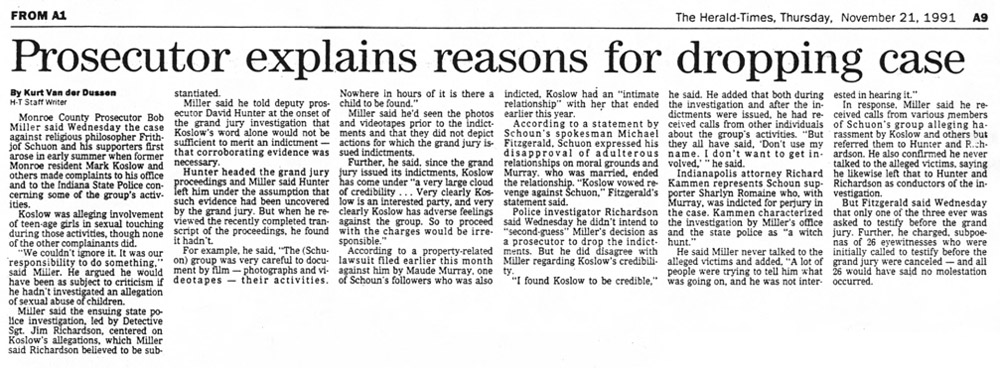

| November 21, 1991 | Prosecutor explains reasons for dropping case |

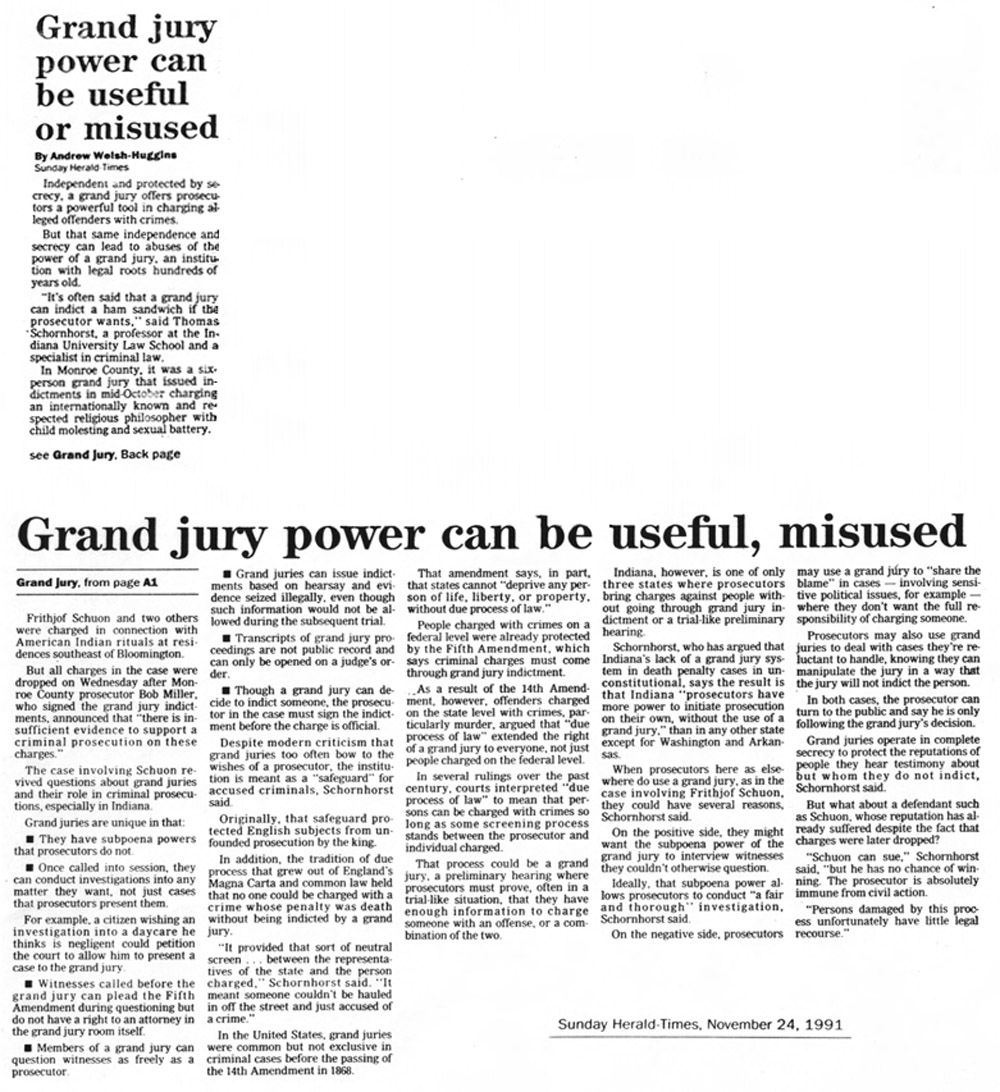

| November 24, 1991 | Grand jury power can be useful, misused |

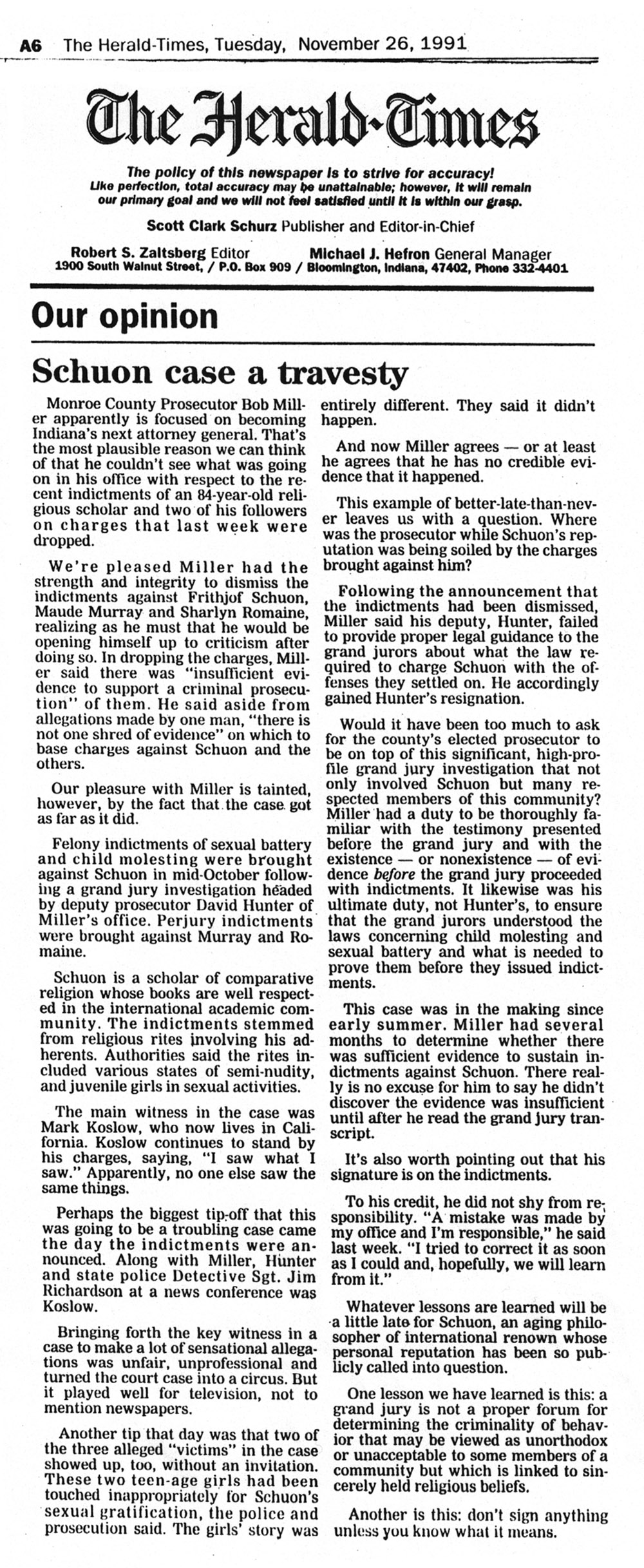

| November 26, 1991 | Schuon case a travesty |

| May 17, 1998 | Spiritual leader Schuon leaves message of religious unity |

Readers can also view or download all of these reports in a single pdf document.

Abuse Charges Aired, Denied

A man who described himself as a former member of a Bloomington-based “cult” that incorporated elements of Christian, Muslim and Native American religious rites said Tuesday the group’s leader is “a fake who abused children.”

Speaking before television, radio and newspaper reporters at a 10 a.m. Justice Building news conference, Mark Koslow said 84-year-old Swiss philosopher Frithjof Schuon was a “crazy genius” who “fooled people of quite eminent standing all over the world.”

Schuon, Road, surrendered himself to police Tuesday after being indicted on charges of sexual battery and child molestation following a six-week grand jury investigation. The jury concluded last week, and the indictment was unsealed late Monday night.

Schuon said Tuesday he is a philosopher, not a religious leader, and denied the charges.

Koslow, 35, said he came to Bloomington from the San Francisco, Calif., area 2-1/2 years ago in order to be near Schuon who lives in the subdivision southeast of Bloomington.

Koslow said he’d read Schuon’s books for several years and was attracted to the “spiritual promises” they offered.

During his time with Schuon, Koslow built frames for paintings done by Schuon and worked “as a general handyman, doing odd jobs for the group,” Koslow said.

He described participating in rituals in which nude women danced in a circle around Schuon and were in some cases embraced by Schuon.

The indictment alleges that on two of these occasions, in March and May, Schuon fondled three girls aged 13, 14 and 15 “with intent to arouse sexual desire.”

Koslow also described Schuon as a man addicted to power who “thinks he’s sort of like God,” and who believes “he embodies the divine intellect.”

Detective Sgt. Jim Richardson of the Indiana State Police said he began his investigation in July after receiving a complaint about Schuon and the group members called the Mariamiah.

The detective said he interviewed more than 30 witnesses in the case and conducted a search of the residence of Sharlyn Romaine, Road, one of two other people named in the indictments. He recovered “photographic evidence of rituals” during that search, Richardson said.

Asked repeatedly by reporters why he came forward, Koslow said he didn’t do it for the publicity and that he hated cameras. “I decided to talk about this because the man should be exposed as a fake,” Koslow said.

He added that he arrived at this conclusion after becoming romantically involved with Maude Murray, Road, another follower of Schuon and the third person named in Tuesday’s indictments. Murray and Romaine are accused of perjuring themselves during testimony before the grand jury.

Koslow said he learned things from Murray about Schuon that disturbed him, but that Murray “was telling me (these things) in the context of telling me about the nature of a great prophet,” and not to criticize Schuon, he said.

About 70 people were connected with Schuon in Bloomington, of whom about 20 were out-of-towners like himself who came to Bloomington solely to be with Schuon, he said.

Near the end of Tuesday’s news conference, two girls aged 14 and 15 who said they were two of the girls described in the indictment held their own conference in the Justice Building where they angrily denounced Koslow and state police, saying the alleged incidents never occurred. They would not give their names, however.

Richardson said he could not say whether the girls or the defendants appeared before the grand jury, but he said Koslow was the only person who alleged that the girls were touched.

Late Tuesday morning, satellite vans and reporters from Indianapolis and Terre Haute television stations crowded the scenic entrance to the subdivision . Several residents who were home shooed reporters off their property.

Tuesday night, Bloomington businessman Michael Fitzgerald called Koslow’s allegations “monstrous and full of lies.”

Fitzgerald, who said he is a friend of Schuon who first read the philosopher’s books as a freshman at Indiana University in 1968, said Koslow’s motive is vengeance.

“He wants to kill an 84-year-old man who’s had three heart attacks by putting him through the process of these proceedings and by destroying his reputation,” Fitzgerald said.

Fitzgerald also refuted the idea that an organized group exists under Schuon’s leadership. “We are friends of Mr. Schuon who are trying to live a moral and upright life based on his spiritual principles,” he said. He added: “We should be very honored to have this man living among us.”

Fitzgerald also slammed the state police for not informing any of the three defendants of the exact charges against them until Tuesday, “when they read about it in your newspaper.”

He also accused state police and Monroe County Prosecutor Bob Miller of staging a “circus” Tuesday morning by calling a news conference and not allowing the three to turn themselves in until after the conference, when the media were still present at the Justice Building.

Richardson said he called Sharlyn Romaine’s attorney on Friday to inform her of the indictment, though not the specific charge. He said Schuon’s attorney called him on Friday. Richardson said he called Maude Murray on Monday before noon.” If they’re saying they weren’t advised then they’re overpaying their attorneys,” he said.

Schuon Well Known Among Religious Scholars

Frithjof Schuon is a scholar, artist, poet and author who has published more than a dozen books on mysticism, philosophy and unity among diverse religious beliefs.

Ever since he was a boy, the 84-year-old Schuon has been interested in religious and metaphysical questions. He is quoted in the reference book Contemporary Authors as saying he is “fascinated by the problem of the esoteric unity of religions.”

He proclaims an interest in preserving the traditional religious beliefs and culture of the American Indians. Called “Shaykh Isa Nurradin Achmed” in Islam, Schuon said he has been adopted by two Sioux Indian tribes that have given him the names “Brave Eagle” and “Bright Star.”

He writes about a unity of religion that transcends the doctrines of particular religious beliefs.

Schuon is well known in the world of religious studies. The Encyclopedia of Religion refers to him as one of the “great European Sufi masters.” Sufism is a form of Islam focusing on mysticism — the search for insight into spiritual truths beyond human understanding through reason.

Scott Alexander, an Indiana University lecturer specializing in Islam, has read several of Schuon’s books. He said that Schuon, because of his belief in a common ground for many religions, is not one of the highest-renowned religious scholars of the world.

But he said Schuon is on the periphery and is respected by his peers. “He is a sophisticated thinker, but he has an agenda of his own in believing that religions have this common thread,” Alexander said. “That’s what’s moved his scholarship to the edge in religious studies circles. But he’s not some fly-by-night leader. He has had a profound influence and is recognized as an accomplished scholar.”

He did not have information about and could not describe the religious doctrines Schuon and his followers believe in.

Schuon has been in Bloomington about 10 years. Of German heritage, he was born in Basel, Switzerland, where his father was a concert violinist. In 1949, he married Catherine Feer, a painter.

He studied philosophy, Arabic and comparative religion, and has been a writer since 1934. The latest edition of Contemporary Authors says that besides writing, he designs printed textiles and paints portraits of American Indians.

As a young man, he was a student of the Algerian Sufi leader Ahmad Al-Allawi. He also studied religion in Morocco, North Africa, Egypt, Turkey, India and the western United States. Throughout his life, he has worked to document the unity of religions to shore up his belief that a common factor underlies the most diverse spiritual theologies.

Alexander said the cultivation of that belief is what Schuon is best known for. “I don’t know just what his particular religious beliefs are. There’s all kinds of scuttlebutt,” he said. “I suppose he could be considered a comparative religionist.”

Schuon’s writings extensive

The philosopher who was indicted Tuesday on charges of allegedly molesting three teenage girls as part of a religious ritual has an established publishing record as a religious philosopher.

Frithjof Schuon, 84, Road, who is believed to be a religious leader in Bloomington, has published more than a dozen books about the connections between different religious philosophies during the last half century, according to a check of IU library holdings.

The IU Main Library research section contains 13 different titles by Schuon.

An IU professor who is familiar with Schuon’s work said he found the criminal charges filed against Schuon difficult to believe.

“It would be wild speculation that would lead to any connection between his writings and these allegations (of child molesting),” said Jim Hart, religious studies associate professor.

Hart described Schuon as an “extremely learned” scholar who has received widespread recognition for his work.

“He is generally considered one of the leaders in the universal interpretation of religions,” Hart said. “Apart from this matter, Bloomington should be honored that (Schuon) chose to make his abode among us.”

Hart said he was unaware Schuon was in Bloomington until the charges were filed.

Schuon is free on bond while facing felony charges of child abuse and sexual battery for allegedly fondling three Bloomington girls in the spring.

Two followers of Schuon have been charged with perjury for allegedly lying to a Monroe County grand jury during its investigation of the case. The grand jury handed down the indictments Tuesday.

Hart criticized media coverage of the case.

“In this community, even a whiff of a commune sets off wild speculation,” he said.

Schuon was born in Basle, Switzerland, in 1907 and moved to Bloomington from Switzerland six years ago, said Indiana State Police Detective Sgt. Jim Richardson.

Richardson said it is “not surprising” that some people are rallying to Schuon’s defense.

“That’s almost the norm when dealing with a non-traditional group” such as Schuon and his supporters, he said.

Schuon has studied in Paris and has traveled to north Africa, the Middle East and the American West to study with different religious philosophers, according to the jacket on his latest book, “In the Face of the Absolute.” The book was published by Bloomington-based World Wisdom Books.

Schuon is scheduled Wednesday for an initial hearing on the charges before the Monroe County Circuit Court.

Schuon known as an ‘eminent thinker’

For most people in the Bloomington area, their first introduction to Swiss philosopher Frithjof Schuon was news of his arrest Tuesday on charges of sexual battery and child molesting.

Indicted following a six-week grand jury investigation, the 84-year-old Schuon, a private man in poor health, was momentarily thrust into the public eye.

The 84-year-old Schuon had moved with his wife Catherine to Bloomington in September 1980 from Lausanne, Switzerland.

For the past 11 years he lived quietly, surrounded by followers and admirers in a house in , a wealthy subdivision southeast of Bloomington.

But a grand jury indictment issued last week changed that forever.

The indictments charge that between March 23 and 27 and again on May 17, Schuon and alleged religious followers compelled three teen-age girls to submit to fondling. Two women were also charged with lying to the grand jury during the course of its investigation.

Schuon has heatedly denied the charges, and friends earlier in the week denounced the allegations as “monstrous and full of lies.”

Since then, friends of Schuon as well as Schuon himself have declined to comment for an article about the philosopher, citing the advice of their attorney.

But Seyyed Hossein Nasr, an editor and long-time acquaintance of Schuon, said Friday: “He belongs to a different world. He is very much a ‘pre-modern’ man.”

Nasr, 58, University Professor of Islamic Studies at George Washington University, edited The Essential Writings of Frithjof Schuon as well as a book of essays collected in honor of Schuon’s 80th birthday.

Reached by phone at his office in Washington, D. C., Nasr described Schuon as an aloof, private man who prefers to let his books speak for themselves.

Nasr said he began reading Schuon’s books as a student at Harvard University in the 1950s. Later he traveled to Lausanne and visited with Schuon.

“He was very much born and bred in the culture of 19th-century Europe,” Nasr said. “He is opposed to modern civilization, and keeps himself distant from the problems of the modern world.”

As a philosopher and scholar of religions, Schuon was a defender of traditional religions, a school of thought “based on the thesis that truth resides as revealed in all major religions,” Nasr said.

Schuon was born in Basel, Switzerland in 1907, the son of German parents, according to a short biography of Schuon by Nasr, published in 1980 as a preface to Religion of the Heart: Essays presented to Frithjof Schuon on his Eightieth Birthday.

Schuon received some schooling in Switzerland but later moved with his widowed mother to the city of Mulhouse in Alsace where he became a French citizen.

As a teen he read German philosophers, Plato, the Bhagavad-Gita and the Upanishads, among countless other philosophical and religious works.

But “the rigid and lifeless educational curriculum” convinced him to leave school at the age of 16, according to Nasr’s biography. Schuon worked briefly as a textile designer, then spent 1-1/2 years in the French Army.

After he was discharged, he settled in Paris and continued working as a designer. It was in Paris he began to study Arabic and Islamic culture.

In 1932 Schuon visited Algeria where, Nasr writes, he “experienced his first direct encounter with the Islamic world and was able to gain intimate knowledge of the Islamic tradition from within.”

Schuon traveled twice more to North Africa in 1935 and 1938, then visited India.

World War II forced him back to France where he rejoined the French Army. He was captured and imprisoned by the Germans, then nearly inducted into the German army because of his Alsatian origin. Instead he fled to Switzerland.

In Lausanne in 1949 he married Catherine, daughter of a Swiss ambassador. The two did not have children.

For the next 40 years he wrote and painted in Lausanne, slowly developing his reputation as “a very, very eminent thinker, metaphysician and philosopher,” Nasr said.

“I’ve always considered Frithjof Schuon the most important expositor of metaphysical truth in this century.”

Nasr recalled that visiting Schuon in Lausanne, “he was very withdrawn. He kept to himself and his house, occasionally coming out to go for a walk.”

One of his most famous books, The Transcendent Unity of Religions, first published in 1948, garnered the praise of no less an intellectual authority than poet T. S. Eliot, who wrote: “I have met with no more impressive work in the comparative study of Oriental and Occidental religions.”

Most of Schuon’s books and articles appeared first in French and were later translated to English and other languages, including German, Italian, Portuguese, Arabic and Malay.

His publishers include Penguin, Harper and Row, and Allen and Unwin, as well as World Wisdom Books in Bloomington, a company that currently only publishes books by Schuon.

In 1959 and again in 1963 Schuon and his wife visited Indian reservations in Montana and South Dakota.

Nasr said Friday that Schuon’s introduction to Joseph Brown’s book about Sioux holy man Black Elk is “the most important exposition of Native American religion and its metaphysical and cosmological consequences” ever written.

In a statement issued after his arrest, Schuon said his “personal affinity is for the Red Indian cultural form” but he did not require anyone to follow that affinity.

Nasr said he’d learned two weeks ago of the investigation into Schuon and his followers.

“I have to express my personal sadness at this episode, which is very difficult to understand,” he said.

Judge: Schuon charges vague

The judge handling the child molestation case of a Bloomington religious leader criticized the grand jury’s indictment against the leader Monday, calling it vague and misleading.

“This indictment is confusing to me,” Monroe County Circuit Court Judge James M. Dixon told the defendant in the case, Frithjof Schuon, of Road during an initial hearing.

The indictment charges Schuon, 84, with one count of child molesting and one count of sexual battery for allegedly “fondling or touching” three teenage girls “by undue cult influences” on at least two separate occasions last spring.

Dixon automatically entered a plea of not guilty for Schuon during the hearing, in front of more than 50 Schuon supporters, who had packed the courtroom.

“(The indictment) leads me to believe that you committed six separate counts. But the state has only charged you with one count,” Dixon said to Schuon.

“It’s hard for me to determine what proof must be made for you to be found guilty,” he said.

Dixon told Schuon’s attorneys to file a motion for a more detailed indictment before the trial begins.

Schuon’s attorney, Dennis Zahn, was not surprised by Dixon’s reaction. “We thought there would be a number of problems with it in addition to what Judge Dixon said,” he said. In the past, the attorneys have described the charges as witch hunts against Schuon.

Assistant Prosecutor David Hunter declined to comment on Dixon’s reaction.

Schuon, who moved to Bloomington from Switzerland 10 years ago, is an internationally known religious philosopher whose books express a universal connection between different faiths.

Your Opinion: Charges ‘bizarre’

To the editor:

Ever since I came upon his writings 20 years ago, Mr. Frithjof Schuon has been the most important intellectual and spiritual influence in my life. As a member of the nominating board of the prestigious Grawemeyer Award for religious literature, mounted by the University of Louisville, I last year nominated The Essential Writings of Frithjof Schuon as the most important book on religious thought to appear in the last three years. I regularly begin each day by reading, first, a passage from sacred scripture, and follow this with something written by Mr. Schuon, for he “feeds my soul,” as the saying goes, as does no other living religious writer.

During the last two decades I have sought out Mr. Schuon a number of times for intellectual and spiritual counsel, and though my visits have always been brief, I have become acquainted with a number of his followers in Bloomington and elsewhere who include in their ranks some of the most gifted and respected religious scholars of our day. As the author of the most widely used textbook on world religions for the last 30 years (The Religions of Man, now retitled The World’s Religions), I think I know enough not only about Mr. Schuon and his followers but about the subject generally, to say that the charge (as reported to me by telephone this week) that he heads a “degenerate cult,” is bizarre in the extreme. The same holds, as far as I can tell, for the charge of “thought control.” Mr. Schuon has profoundly influenced my thought, but he has never attempted to control it.

As for sexual perversion, all I can say is that it would run counter to Mr. Schuon’s entire corpus which enjoins moral purity as the foundation and indispensable prerequisite for the religious life.

Huston Smith

Berkeley, Calif.

Witness against Schuon sued by indicted woman

The California man whose testimony against 84-year-old religious philosopher Frithjof Schuon led to Schuon’s indictment on child molesting and sexual battery charges has been sued in Monroe Circuit Court by a woman indicted by the grand jury at the same time for alleged perjury.

Maude Murray of Road had filed the suit against Mark Koslow. It alleges that Koslow bought property for Murray with her money during a relationship the two had, but has refused to convey her the deed for it after the relationship ended.

Koslow could not be reached for comment on the lawsuit. His whereabouts between Bloomington and California are unknown, according to his mother in , Ohio, and Indiana State Police Sgt. Jim Richardson, who has been in contact with Koslow throughout the state police investigation of Schuon and his alleged spiritual activities.

Murray is one of two female supporters of Schuon indicted by the grand jury in October for perjury. The two allegedly testified they had not spoken to anyone about getting “a spiritual divorce” from Schuon, knowing their testimony was false.

The indictments against Schuon allege that on two occasions in March and May, he committed child-molesting and sexual battery by “fondling or touching” three teen-age girls for sexual arousal during alleged ceremonies involving Schuon and adherents living in southeast of Bloomington.

According to the indictments, the sexual battery occurred when the three teen-age girls “were compelled to submit to touching by force or imminent threat of force, to wit, by undue cult influences and cult pressures.” Schuon has bitterly denied the allegations, as have his supporters.

Schuon’s supporters have accused Koslow of bringing the allegations against Schuon out of revenge for Schuon’s refusal to give his blessing to a relationship Koslow sought.

Murray’s lawsuit alleges that between August 1990 and June 1991, Murray and Koslow had “an intimate relationship.” During that relationship, she alleges, she authorized Koslow to buy land for her at 7414 Pine Grove Road and subsequently gave him more than $67,000 to do so, which she says he did. She said Koslow was to hold the land in trust for her for a future residence.

Murray alleges that Koslow subsequently has refused to convey title to the property to her. She is asking Judge Marc Kellams to order him to do so.

Further, she alleges she paid Koslow $3,500 for his handling of the property acquisition for her, and she seeks that money back as well.

She also alleges she entrusted other property to Koslow, but that he has refused to return it as well. She alleges that constitutes “criminal conversion” and entitles her to triple damages.

Murray alleges she would never have entrusted her money to Koslow if she did not have “trust and confidence” in him based on his representations and her belief that he intended to marry her. She alleges he had no such intent and thus fraudulently gained control over her money.

Schuon indictments dropped

Indictments charging child molesting and sexual battery against international religious scholar and philosopher Frithjof Schuon issued by a Monroe County grand jury last month were dismissed Wednesday by Prosecutor Bob Miller.

In addition, perjury indictments against two members of Schuon’s group of adherents and supporters, Maude Murray and Sharlyn Romaine, were dismissed.

Miller also said the deputy prosecutor who headed the grand jury investigation, David Hunter, has submitted his resignation.

After reviewing a transcript of the grand jury proceedings plus available evidence, Miller concluded “there is insufficient evidence to support a criminal prosecution on these charges.”

Miller said that other than the testimony of one individual, Mark Koslow, now living in an undisclosed location in the West, “there is not one shred of evidence” upon which a criminal case could be prosecuted against Schuon.

“Insofar as he has been labeled (by the allegations), a miscarriage has occurred,” Miller said.

Schuon’s spokesman, Michael Fitzgerald, agreed. In a statement released Wednesday on Schuon’s behalf, he said it was “an affront to justice” that nobody listened to the defendants prior to raising “these disgraceful and unfounded allegations.” The investigation and indictments, he said, were “an outrage to the intellectual and moral reputation of Bloomington.”

Schuon, 84, of Road, is a scholar of comparative religion whose books have an international academic reputation. He was indicted in October by a grand jury following a two-month investigation into allegations of religious rites involving his adherents in various states of semi-nudity and involving juvenile girls in sexual activities.

The indictments against Schuon alleged that on March 23-27 and again on May 17, Schuon committed child-molesting by “fondling or touching” three girls aged 15, 14 and 13 with intent to arouse sexual desire.

They also alleged that on the same dates, Schuon committed sexual battery by touching the girls with intent to arouse sexual desire, “when said persons were compelled to submit to touching by force or imminent threat of force, to wit, by undue cult influences and cult pressures.”

Both indictments were felonies, punishable by up to three years in prison and/or a fine of up to $10,000.

The indictments for perjury against Murray, of Road, and Romaine, of Road, alleged that on Sept. 30, both women knowingly made false statements to the grand jury that they had not spoken to anyone about getting “a spiritual divorce” from Schuon.

The three already had entered pleas of innocence to the charges. In addition, all three girls and their parents had called the allegations untrue.

At Schuon’s initial court hearing on Oct. 28, a frustrated Monroe Circuit Judge James Dixon had told Schuon he couldn’t tell him what the state would have to prove to convict him because the charges were confusing. Dixon said it appeared to him conviction on either count would require the state to prove six distinct illegal acts. Miller said later that day the indictments would be amended.

But Wednesday morning, Miller announced he was dismissing them totally. He issued a statement explaining that upon his “personal review” of the grand jury transcript, “I have concluded that there is insufficient evidence to support a criminal prosecution of these charges,” and that the indictments were being dismissed.

Miller’s statement continued:

“My decision is based on the fact that, other than the allegations of the original complaining witness (Koslow), there is simply no other evidence to support these charges. Considering the public statements of the defendants, as well as those of the alleged victims, the uncorroborated allegations of the complainant are not sufficient to justify further involvement of the justice system.

“It is my firm belief that the grand jury acted in good faith in their consideration of the evidence presented to them and in a manner consistent with a lay person’s reaction. However, in our system of justice there is no place for the old adage, ‘Where there’s smoke, there’s fire.’ The grand jurors were also correct in pointing out the misstatements which form the basis of the perjury indictments. However, these misstatements were neither significant or material as is required by law to support a charge of perjury.

“Bloomington has long been a community which welcomes cultural diversity and freedom of expression. That is why I stated at the time the indictments were returned that my only interest in the activities of this group extended to the possible involvement of children. The evidence in my possession at this time does not support that allegation.

“What the evidence does indicate is that the group is engaged in activities that are protected by the First Amendment and should be respected in a community that values the free flow of ideas. The behavior of consenting adults in the privacy of their own homes must be considered the most fundamental of liberties guaranteed under our constitutional system.”

Miller said part of the problem with the grand jury indictments was that Hunter had failed to give the jurors “appropriate direction about the law and its requirements,” which resulted in inappropriate indictments.

He said Hunter resigned his position last week. Asked if he requested Hunter’s resignation, Miller replied, “I will not make any further comment, and will leave it to people to drawn their own conclusions.”

Hunter blamed Miller.

“The indictment has his signature on it,” he said Wednesday. “He approved the wording of the indictment. It was he who initiated the grand jury investigation. When it started, he explained to the grand jury what he wanted. He only turned it over to me to finish it up after he got tired of being in there. So I find his explanation novel if not startling.”

Miller differed with that, saying the case was brought to Hunter by the state police. He said his own sole role during the six weeks of grand jury hearings was to question Koslow before the jurors on the first day.

“That was it,” he said, though he did confirm he signed the indictments.

“There’s no question that I’m taking responsibility for what happened here,” said Miller. But he said he needs to trust his subordinates, and that in this case, he acted as rapidly as he could to correct mistakes by a member of his staff.

Indianapolis attorneys Dennis Zahn and Jim Voyles, who represent Schuon, were in court Wednesday and could not be reached for comment. Indianapolis attorney Richard Kammen, who represented Romaine, was highly critical of Miller.

“I think there’s some really serious questions that have to be addressed as to how Mr. Miller runs his office,” he said. “This has been as abusive and disgraceful a procedure as it could be. At the least, he owes the defendants a very grave apology.”

In an interview telecast Wednesday night on WTHR Channel 13, Miller said that “certainly an apology of sorts” was called for. Miller said Wednesday night that his statement reflected his regret that “the system broke down.”

Asked if the former defendants were considering civil actions, Kammen replied, “We’re in the process of weighing all the available options.”

Schuon’s spokesman Fitzgerald said the state police have already been contacted and asked to pursue disciplinary action against Detective Sgt. Jim Richardson, who headed the investigation, for abusing the defendants’ civil rights. The disciplinary action could be “an alternative to remedies through the courts,” which he said Schuon would prefer to avoid, Fitzgerald said. But he said a federal civil rights lawsuit has been suggested by at least one legal expert.

Richardson and Miller both maintained the state police investigation was properly conducted, with its findings handled in the normal manner and submitted to the grand jury as they should have been.

Schuon happy ‘nightmare’ is over

For the first time in almost a year, Frithjof Schuon has a sense of peace and relief.

Schuon, 84, is a Swiss religious philosopher who moved to Bloomington 11 years ago.

It was in December 1990, he and supporters say, that a former follower vowed to seek revenge on Schuon for disapproving of an adulterous affair the follower was having.

Schuon believes that revenge culminated in a mid-October grand jury indictment charging the philosopher with sexual battery and child molesting in connection with American Indian rituals near Schuon’s home on Road in southeast Bloomington.

On Wednesday, all charges against Schuon were dropped. Monroe County prosecutor Bob Miller said he had found “insufficient evidence to support a criminal prosecution of these charges.”

In a brief interview Wednesday, Schuon said the announcement ended a “nightmare.”

“It was a terrible atmosphere,” he said. “There was always pressure, a kind of blackmailing pressure.”

He described his accuser, 35-year-old Mark Koslow, as “an awful character, a psychopath … I didn’t think such a creature as Koslow existed.”

Schuon also lashed out at the Indiana State Police for their handling of the case.

“I am astonished. This was not fair. They promoted Koslow, they were sentimentally attached to Koslow. Police should be cold and neutral, not promoting someone,” he said.

At a news conference announcing the charges in October, Koslow also described Schuon as a “cult” leader who exerted enormous control over his followers.

Asked Wednesday if he exerted such control, Schuon said, “Of course! I’m a philosopher, why shouldn’t I? But I’m not a tyrant. Because I disapproved of the relationship, he thought I was a tyrant and brainwashed people.”

Schuon said he has admired American Indian religion, and particularly that of the Plains Indians, for years. He has written extensively about American Indian religion, visited reservations in South Dakota and Montana in the 1950s and 1960s and met with Indian holy men in Europe.

The “primordial” aspects of American Indian religions attracted him, Schuon said. Such religions are without theology and hairsplitting and based on “metaphysics” and prayer, he said. American Indian religion also conforms with his belief in the existence of “one hidden religion … the same truth hidden in all forms.”

“Indians have a strong feeling of transcendence and universality,” he said. “The Great Spirit is above all forms and yet present in all forms.”

Reached by telephone Wednesday night in the Oakland, Calif., area, Koslow denied that revenge was his motive in making the initial complaints to state police.

He called Schuon a “false spiritual master” whom he decided to expose as a way of warning other people about the philosopher. He scoffed at claims by Schuon and his followers that the three teen-age girls Schuon is accused of touching were not in Indiana at the time of the alleged incidents.

“I saw what I saw, I know what I know,” Koslow said. He also said he was not surprised the charges were dropped.

“I was saying all along if Schuon was just indicted I wouldn’t care if he wasn’t convicted. I knew I was the only one with the courage to come out against him,” Koslow said.

Schuon, the author of more than 20 books on comparative religion, said Wednesday he is too “exhausted” to do much writing now. Instead, he spends his days now praying and resting.

“I am a philosopher, I write books,” he said of his life’s work.

“I have a certain gift of intuition, of moral and spiritual intuition.”

Prosecutor explains reasons for dropping case

Monroe County Prosecutor Bob Miller said Wednesday the case against religious philosopher Frithjof Schuon and his supporters first arose in early summer when former Monroe resident Mark Koslow and others made complaints to his office and to the Indiana State Police concerning some of the group’s activities.

Koslow was alleging involvement of teen-age girls in sexual touching during those activities, though none of the other complainants did.

“We couldn’t ignore it. It was our responsibility to do something,” said Miller. He argued he would have been as subject to criticism if he hadn’t investigated an allegation of sexual abuse of children.

Miller said the ensuing state police investigation, led by Detective Sgt. Jim Richardson, centered on Koslow’s allegations, which Miller said Richardson believed to be substantiated.

Miller said he told deputy prosecutor David Hunter at the onset of the grand jury investigation that Koslow’s word alone would not be sufficient to merit an indictment — that corroborating evidence was necessary.

Hunter headed the grand jury proceedings and Miller said Hunter left him under the assumption that such evidence had been uncovered by the grand jury. But when he reviewed the recently completed transcript of the proceedings, he found it hadn’t.

For example, he said, “The (Schuon) group was very careful to document by film — photographs and videotapes — their activities. Nowhere in hours of it is there a child to be found.”

Miller said he’d seen the photos and videotapes prior to the indictments and that they did not depict actions for which the grand jury issued indictments.

Further, he said, since the grand jury issued its indictments, Koslow has come under “a very large cloud of credibility … Very clearly Koslow is an interested party, and very clearly Koslow has adverse feelings against the group. So to proceed with the charges would be irresponsible.”

According to a property-related lawsuit filed earlier this month against him by Maude Murray, one of Schuon’s followers who was also indicted, Koslow had an “intimate relationship” with her that ended earlier this year. According to a statement by Schuon’s spokesman Michael Fitzgerald, Schuon expressed his disapproval of adulterous relationships on moral grounds and Murray, who was married, ended the relationship. “Koslow vowed revenge against Schuon,” Fitzgerald’s statement said.

Police investigator Richardson said Wednesday he didn’t intend to “second-guess” Miller’s decision as a prosecutor to drop the indictments. But he did disagree with Miller regarding Koslow’s credibility.

“I found Koslow to be credible,” he said. He added that both during the investigation and after the indictments were issued, he had received calls from other individuals about the group’s activities. “But they all have said, ‘Don’t use my name. I don’t want to get involved,’ ” he said.

Indianapolis attorney Richard Kammen represents Schuon supporter Sharlyn Romaine who, with Murray, was indicted for perjury in the case. Kammen characterized the investigation by Miller’s office and the state police as “a witch hunt.”

He said Miller never talked to the alleged victims and added, “A lot of people were trying to tell him what was going on, and he was not interested in hearing it.”

In response, Miller said he received calls from various members of Schuon’s group alleging harassment by Koslow and others but referred them to Hunter and Richardson. He also confirmed he never talked to the alleged victims, saying he likewise left that to Hunter and Richardson as conductors of the investigation.

But Fitzgerald said Wednesday that only one of the three ever was asked to testify before the grand jury. Further, he charged, subpoenas of 26 eyewitnesses who were initially called to testify before the grand jury were canceled — and all 26 would have said no molestation occurred.

Grand jury power can be useful or misused

Independent and protected by secrecy, a grand jury offers prosecutors a powerful tool in charging alleged offenders with crimes.

But that same independence and secrecy can lead to abuses of the power of a grand jury, an institution with legal roots hundreds of years old.

“It’s often said that a grand jury can indict a ham sandwich if the prosecutor wants,” said Thomas Schornhorst, a professor at the Indiana University Law School and a specialist in criminal law.

In Monroe County, it was a six-person grand jury that issued indictments in midOctober charging an internationally known and respected religious philosopher with child molesting and sexual battery.

Frithjof Schuon and two others were charged in connection with American Indian rituals at residences southeast of Bloomington.

But all charges in the case were dropped on Wednesday after Monroe County prosecutor Bob Miller, who signed the grand jury indictments, announced that “there is insufficient evidence to support a criminal prosecution on these charges.” The case involving Schuon revived questions about grand juries and their role in criminal prosecutions, especially in Indiana.

Grand juries are unique in that:

- They have subpoena powers that prosecutors do not.

- Once called into session, they can conduct investigations into any matter they want, not just cases that prosecutors present them.

For example, a citizen wishing an investigation into a daycare he thinks is negligent could petition the court to allow him to present a case to the grand jury.

- Witnesses called before the grand jury can plead the Fifth Amendment during questioning but do not have a right to an attorney in the grand jury room itself.

- Members of a grand jury can question witnesses as freely as a prosecutor.

- Grand juries can issue indictments based on hearsay and evidence seized illegally, even though such information would not be allowed during the subsequent trial.

- Transcripts of grand jury proceedings are not public record and can only be opened on a judge’s order.

- Though a grand jury can decide to indict someone, the prosecutor in the case must sign the indictment before the charge is official.

Despite modern criticism that grand juries too often bow to the wishes of a prosecutor, the institution is meant as a “safeguard” for accused criminals, Schornhorst said.

Originally, that safeguard protected English subjects from unfounded prosecution by the king.

In addition, the tradition of due process that grew out of England’s Magna Carta and common law held that no one could be charged with a crime whose penalty was death without being indicted by a grand jury.

“It provided that sort of neutral screen … between the representatives of the state and the person charged,” Schornhorst said. “It meant someone couldn’t be hauled in off the street and just accused of a crime.”

In the United States, grand juries were common but not exclusive in criminal cases before the passing of the 14th Amendment in 1868.

That amendment says, in part, that states cannot “deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.”

People charged with crimes on a federal level were already protected by the Fifth Amendment, which says criminal charges must come through grand jury indictment.

As a result of the 14th Amendment, however, offenders charged on the state level with crimes, particularly murder, argued that “due process of law” extended the right of a grand jury to everyone, not just people charged on the federal level.

In several rulings over the past century, courts interpreted “due process of law” to mean that persons can be charged with crimes so long as some screening process stands between the prosecutor and individual charged.

That process could be a grand jury, a preliminary hearing where prosecutors must prove, often in a trial-like situation, that they have enough information to charge someone with an offense, or a combination of the two.

Indiana, however, is one of only three states where prosecutors bring charges against people without going through grand jury indictment or a trial-like preliminary hearing.

Schornhorst, who has argued that Indiana’s lack of a grand jury system in death penalty cases in unconstitutional, says the result is that in Indiana “prosecutors have more power to initiate prosecution on their own, without the use of a grand jury,” than in any other state except for Washington and Arkansas.

When prosecutors here as elsewhere do use a grand jury, as in the case involving Frithjof Schuon, they could have several reasons, Schornhorst said.

On the positive side, they might want the subpoena power of the grand jury to interview witnesses they couldn’t otherwise question.

Ideally, that subpoena power allows prosecutors to conduct “a fair and thorough” investigation, Schornhorst said.

On the negative side, prosecutors may use a grand jury to “share the blame” in cases — involving sensitive political issues, for example — where they don’t want the full responsibility of charging someone.

Prosecutors may also use grand juries to deal with cases they’re reluctant to handle, knowing they can manipulate the jury in a way that the jury will not indict the person.

In both cases, the prosecutor can turn to the public and say he is only following the grand jury’s decision.

Grand juries operate in complete secrecy to protect the reputations of people they hear testimony about but whom they do not indict, Schornhorst said.

But what about a defendant such as Schuon, whose reputation has already suffered despite the fact that charges were later dropped?

“Schuon can sue,” Schornhorst said, “but he has no chance of winning. The prosecutor is absolutely immune from civil action.

“Persons damaged by this process unfortunately have little legal recourse.”

Our opinion (editorial): Schuon case a travesty

Monroe County Prosecutor Bob Miller apparently is focused on becoming Indiana’s next attorney general. That’s the most plausible reason we can think of that he couldn’t see what was going on in his office with respect to the recent indictments of an 84-year-old religious scholar and two of his followers on charges that last week were dropped.

We’re pleased Miller had the strength and integrity to dismiss the indictments against Frithjof Schuon, Maude Murray and Sharlyn Romaine, realizing as he must that he would be opening himself up to criticism after doing so. In dropping the charges, Miller said there was “insufficient evidence to support a criminal prosecution” of them. He said aside from allegations made by one man, “there is not one shred of evidence” on which to base charges against Schuon and the others.

Our pleasure with Miller is tainted, however, by the fact that the case got as far as it did.

Felony indictments of sexual battery and child molesting were brought against Schuon in mid-October following a grand jury investigation headed by deputy prosecutor David Hunter of Miller’s office. Perjury indictments were brought against Murray and Romaine.

Schuon is a scholar of comparative religion whose books are well respected in the international academic community. The indictments stemmed from religious rites involving his adherents. Authorities said the rites included various states of semi-nudity, and juvenile girls in sexual activities.

The main witness in the case was Mark Koslow, who now lives in California. Koslow continues to stand by his charges, saying, “I saw what I saw.” Apparently, no one else saw the same things.

Perhaps the biggest tip-off that this was going to be a troubling case came the day the indictments were announced. Along with Miller, Hunter and state police Detective Sgt. Jim Richardson at a news conference was Koslow.

Bringing forth the key witness in a case to make a lot of sensational allegations was unfair, unprofessional and turned the court case into a circus. But it played well for television, not to mention newspapers.

Another tip that day was that two of the three alleged “victims” in the case showed up, too, without an invitation. These two teen-age girls had been touched inappropriately for Schuon’s sexual gratification, the police and prosecution said. The girls’ story was entirely different. They said it didn’t happen.

And now Miller agrees — or at least he agrees that he has no credible evidence that it happened. This example of better-late-than-never leaves us with a question. Where was the prosecutor while Schuon’s reputation was being soiled by the charges brought against him?

Following the announcement that the indictments had been dismissed, Miller said his deputy, Hunter, failed to provide proper legal guidance to the grand jurors about what the law required to charge Schuon with the offenses they settled on. He accordingly gained Hunter’s resignation.

Would it have been too much to ask for the county’s elected prosecutor to be on top of this significant, high-profile grand jury investigation that not only involved Schuon but many respected members of this community? Miller had a duty to be thoroughly familiar with the testimony presented before the grand jury and with the existence — or nonexistence — of evidence before the grand jury proceeded with indictments. It likewise was his ultimate duty, not Hunter’s, to ensure that the grand jurors understood the laws concerning child molesting and sexual battery and what is needed to prove them before they issued indictments.

This case was in the making since early summer. Miller had several months to determine whether there was sufficient evidence to sustain indictments against Schuon. There really is no excuse for him to say he didn’t discover the evidence was insufficient until after he read the grand jury transcript.

It’s also worth pointing out that his signature is on the indictments.

To his credit, he did not shy from responsibility. “A mistake was made by my office and I’m responsible,” he said last week. “I tried to correct it as soon as I could and, hopefully, we will learn from it.”

Whatever lessons are learned will be a little late for Schuon, an aging philosopher of international renown whose personal reputation has been so publicly called into question.

One lesson we have learned is this: a grand jury is not a proper forum for determining the criminality of behavior that may be viewed as unorthodox or unacceptable to some members of a community but which is linked to sincerely held religious beliefs. Another is this: don’t sign anything unless you know what it means.

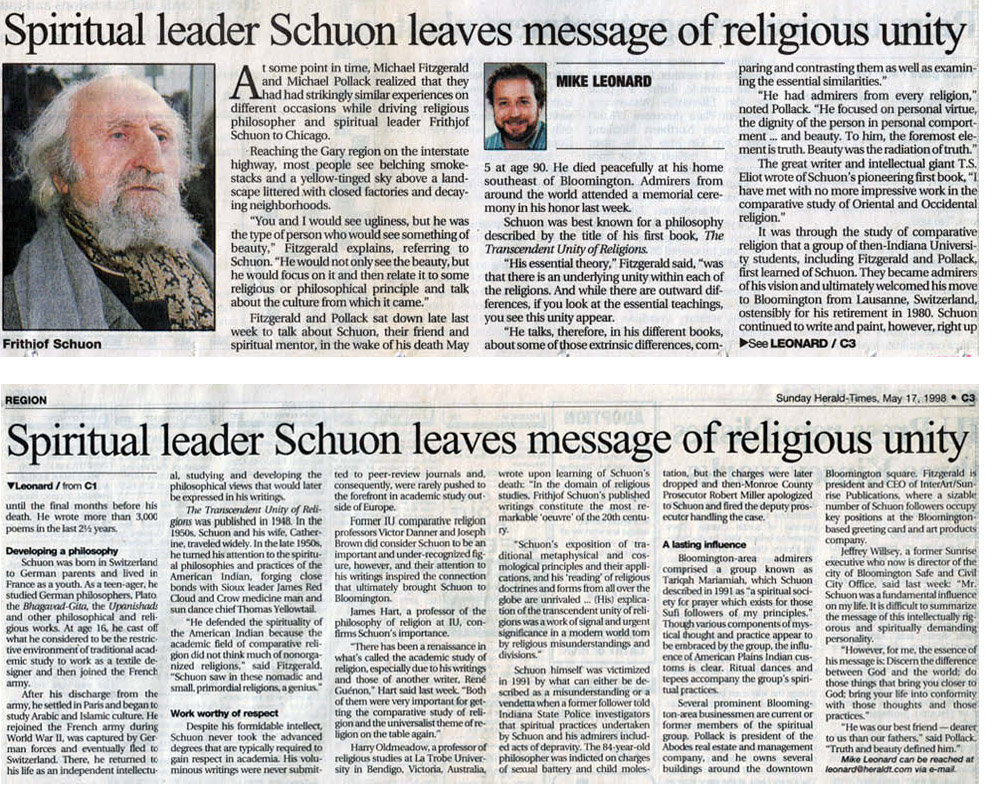

Spiritual leader Schuon leaves message of religious unity

At some point in time, Michael Fitzgerald and Michael Pollack realized that they had had strikingly similar experiences on different occasions while driving religious philosopher and spiritual leader Frithjof Schuon to Chicago.

Reaching the Gary region on the interstate highway, most people see belching smokestacks and a yellow-tinged sky above a landscape littered with closed factories and decaying neighborhoods.

“You and I would see ugliness, but he was the type of person who would see something of beauty,” Fitzgerald explains, referring to Schuon. “He would not only see the beauty, but he would focus on it and then relate it to some religious or philosophical principle and talk about the culture from which it came.”

Fitzgerald and Pollack sat down late last week to talk about Schuon, their friend and spiritual mentor, in the wake of his death May 5 at age 90. He died peacefully at his home southeast of Bloomington. Admirers from around the world attended a memorial ceremony in his honor last week.

Schuon was best known for a philosophy described by the title of his first book, The Transcendent Unity of Religions.

“His essential theory,” Fitzgerald said, “was that there is an underlying unity within each of the religions. And while there are outward differences, if you look at the essential teachings, you see this unity appear.

“He talks, therefore, in his different books, about some of those extrinsic differences, comparing and contrasting them as well as examining the essential similarities.”

“He had admirers from every religion,” noted Pollack. “He focused on personal virtue, the dignity of the person in personal comportment ... and beauty. To him, the foremost element is truth. Beauty was the radiation of truth.”

The great writer and intellectual giant T.S. Eliot wrote of Schuon’s pioneering first book, “I have met with no more impressive work in the comparative study of Oriental and Occidental religion.”

It was through the study of comparative religion that a group of then-Indiana University students, including Fitzgerald and Pollack, first learned of Schuon. They became admirers of his vision and ultimately welcomed his move to Bloomington from Lausanne, Switzerland, ostensibly for his retirement in 1980. Schuon continued to write and paint, however, right up until the final months before his death. He wrote more than 3,000 poems in the last 2 1/2 years.

Developing a philosophy

Schuon was born in Switzerland to German parents and lived in France as a youth. As a teen-ager, he studied German philosophers, Plato, the Bhagavad-Gita, the Upanishads and other philosophical and religious works. At age 16, he cast off what he considered to be the restrictive environment of traditional academic study to work as a textile designer and then joined the French army.After his discharge from the army, he settled in Paris and began to study Arabic and Islamic culture. He rejoined the French army during World War II, was captured by German forces and eventually fled to Switzerland. There, he returned to his life as an independent intellectual, studying and developing the philosophical views that would later be expressed in his writings.

The Transcendent Unity of Religions was published in 1948. In the 1950s, Schuon and his wife, Catherine, traveled widely. In the late 1950s, he turned his attention to the spiritual philosophies and practices of the American Indian, forging close bonds with Sioux leader James Red Cloud and Crow medicine man and sun dance chief Thomas Yellowtail.

“He defended the spirituality of the American Indian because the academic field of comparative religion did not think much of nonorganized religions,” said Fitzgerald. “Schuon saw in these nomadic and small, primordial religions, a genius.”

Work worthy of respect

Despite his formidable intellect, Schuon never took the advanced degrees that are typically required to gain respect in academia. His voluminous writings were never submitted to peer-review journals and, consequently, were rarely pushed to the forefront in academic study outside of Europe.Former IU comparative religion professors Victor Danner and Joseph Brown did consider Schuon to be an important and under-recognized figure, however, and their attention to his writings inspired the connection that ultimately brought Schuon to Bloomington.

James Hart, a professor of the philosophy of religion at IU, confirms Schuon’s importance.

“There has been a renaissance in what’s called the academic study of religion, especially due to his writings and those of another writer, René Guénon,” Hart said last week. “Both of them were very important for getting the comparative study of religion and the universalist theme of religion on the table again.”

Harry Oldmeadow, a professor of religious studies at La Trobe University in Bendigo, Victoria, Australia, wrote upon learning of Schuon’s death: “In the domain of religious studies, Frithjof Schuon’s published writings constitute the most remarkable ‘oeuvre’ of the 20th century.

“Schuon’s exposition of traditional metaphysical and cosmological principles and their applications, and his ‘reading’ of religious doctrines and forms from all over the globe are unrivaled ... (His) explication of the transcendent unity of religions was a work of signal and urgent significance in a modern world torn by religious misunderstandings and divisions.”

Schuon himself was victimized in 1991 by what can either be described as a misunderstanding or a vendetta when a former follower told Indiana State Police investigators that spiritual practices undertaken by Schuon and his admirers included acts of depravity. The 84-year-old philosopher was indicted on charges of sexual battery and child molestation, but the charges were later dropped and then-Monroe County Prosecutor Robert Miller apologized to Schuon and fired the deputy prosecutor handling the case.

A lasting influence

Bloomington-area admirers comprised a group known as Tariqah Mariamiah, which Schuon described in 1991 as “a spiritual society for prayer which exists for those Sufi followers of my principles.” Though various components of mystical thought and practice appear to be embraced by the group, the influence of American Plains Indian customs is clear. Ritual dances and tepees accompany the group’s spiritual practices.Several prominent Bloomington-area businessmen are current or former members of the spiritual group. Pollack is president of the Abodes real estate and management company, and he owns several buildings around the downtown Bloomington square. Fitzgerald is president and CEO of InterArt/Sunrise Publications, where a sizable number of Schuon followers occupy key positions at the Bloomington-based greeting card and art products company.

Jeffrey Willsey, a former Sunrise executive who now is director of the city of Bloomington Safe and Civil City Office, said last week: “Mr. Schuon was a fundamental influence on my life. It is difficult to summarize the message of this intellectually rigorous and spiritually demanding personality.

“However, for me, the essence of his message is: Discern the difference between God and the world; do those things that bring you closer to God; bring your life into conformity with those thoughts and those practices.”

“He was our best friend — dearer to us than our fathers,” said Pollack. “Truth and beauty defined him.”